Heuer’s radical Monaco must have been the ultimate watch alien when it was presented simultaneously at press conferences in Geneva and New York in March 1969. The outside, with its square steel case, was a dramatic break with the classic design cues of the watch industry. The protective housing covered the “all-new gears”: Heuer’s eagerly-awaited automatic movement, powered by a recessed micro rotor.

Rectangular plastic glass – slightly rounded at 6 and 12 o’clock but straight as the Mulsanne at the sides – mirrored the shape of the dramatic top case. The Heuer Monaco was a revolutionary step forward, on the one hand featuring cutting-edge design while on the other solving tough technical challenges with all-new solutions.

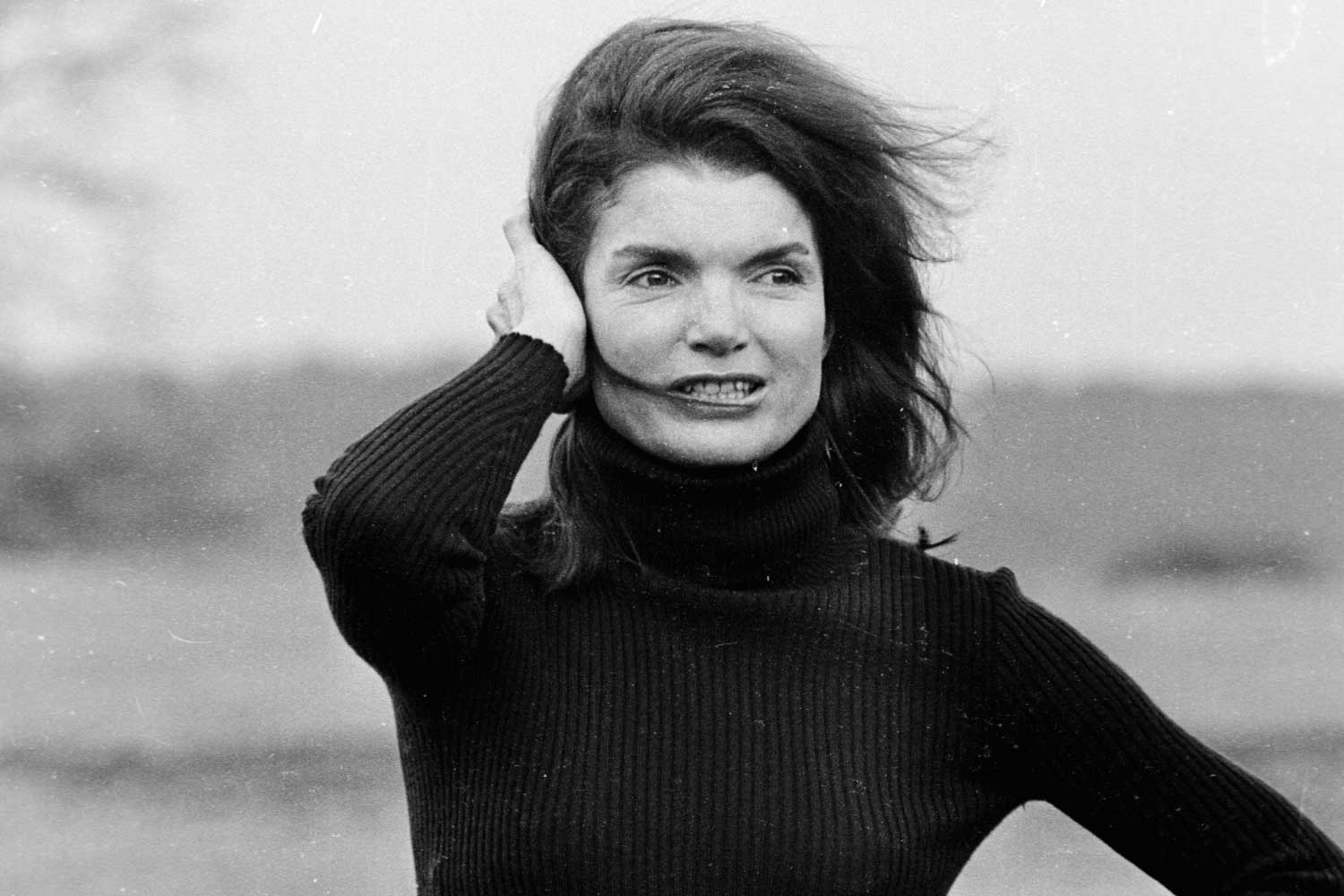

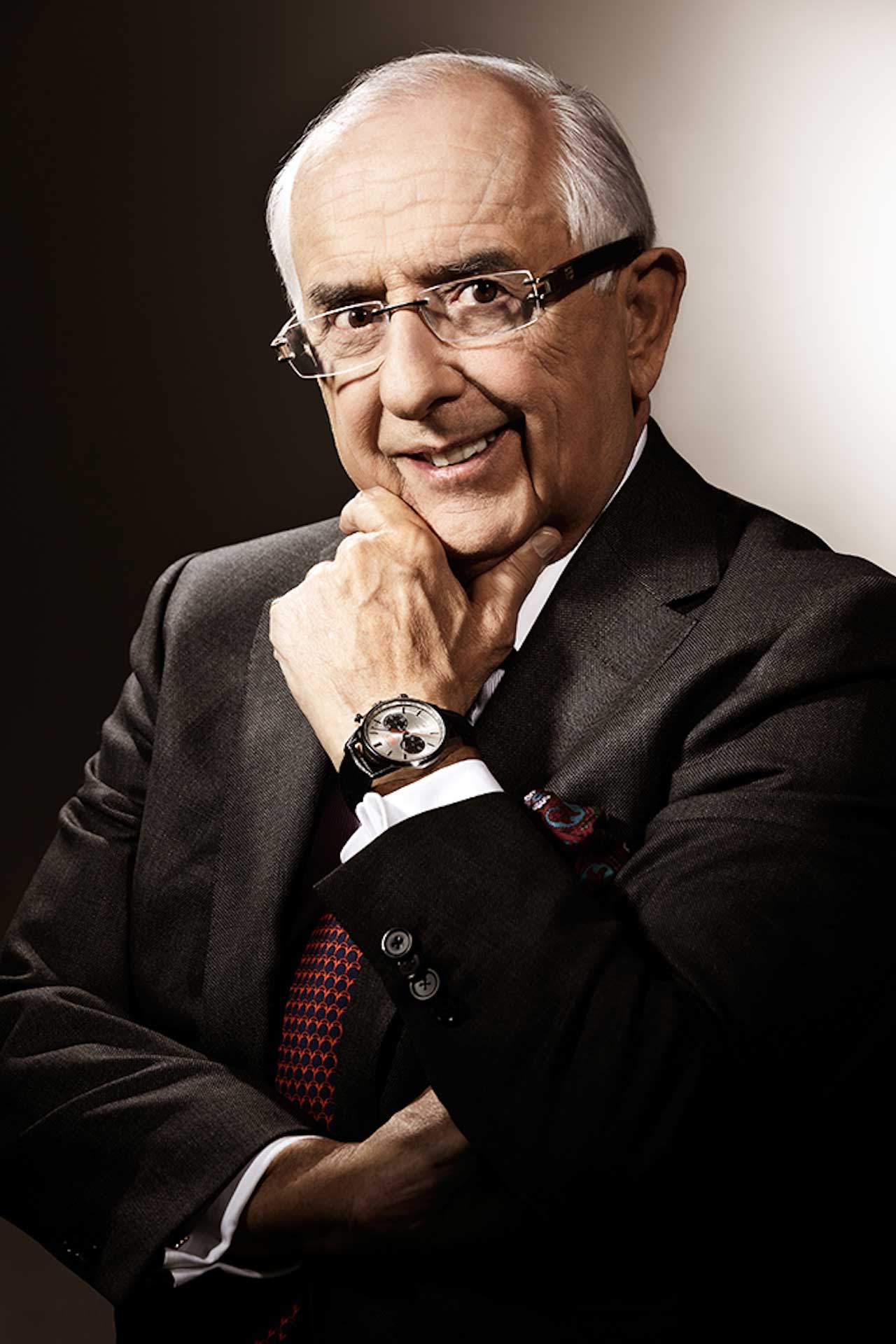

A few years earlier, young Swiss engineer Jack W. Heuer had taken over the family business, Ed Heuer & Co., founded in 1860. He was the driving force at Heuer during the mid-1960s until the 1980s.

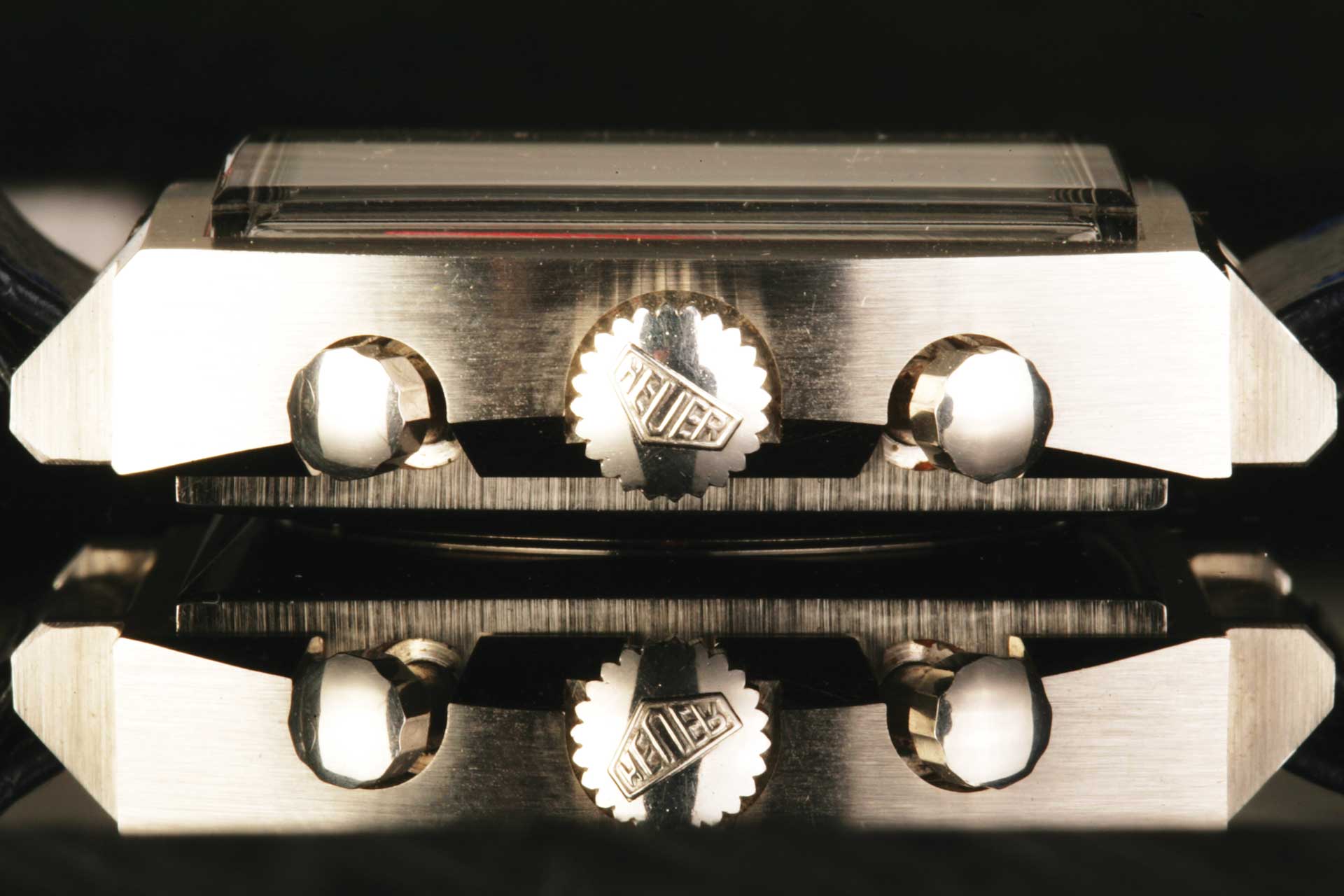

Some time ago at a dinner in Switzerland, Jack shared some background stories. “Until the introduction of the Monaco, all Heuer’s watches had been round, due to the lack of water-resistance in square or barrel-type cases. We started to look into new designs and a case-maker named Piquerez showed us his new waterproofing system for square cases. The key to its success was four notches that clipped into the back and created water-resistance through tension.”

This was an entirely new, patented technique and Heuer negotiated with Piquerez for exclusivity. Thus the Monaco was not only the first square automatic chronograph; it was also the first water-resistant square chronograph watchcase.

A Swiss skiing champion, Jack Heuer was hooked by sports and clearly understood the importance of timekeeping. Team managers and racetrack officials knocked at his door to get more and more precise timing instruments. Heuer dashboard-mounted timers were already used in aviation and racing cars. The legendary Monte Carlo timers were put to use in Minis and Porsche rally cars. The next move, however, was into F1 and this came about by discussions with fellow Swiss racing driver Jo Siffert. By lucky coincidence, Siffert had a Porsche dealership in Fribourg and he was also organising cars and stunt drivers for the filming of the epic movie Le Mans.

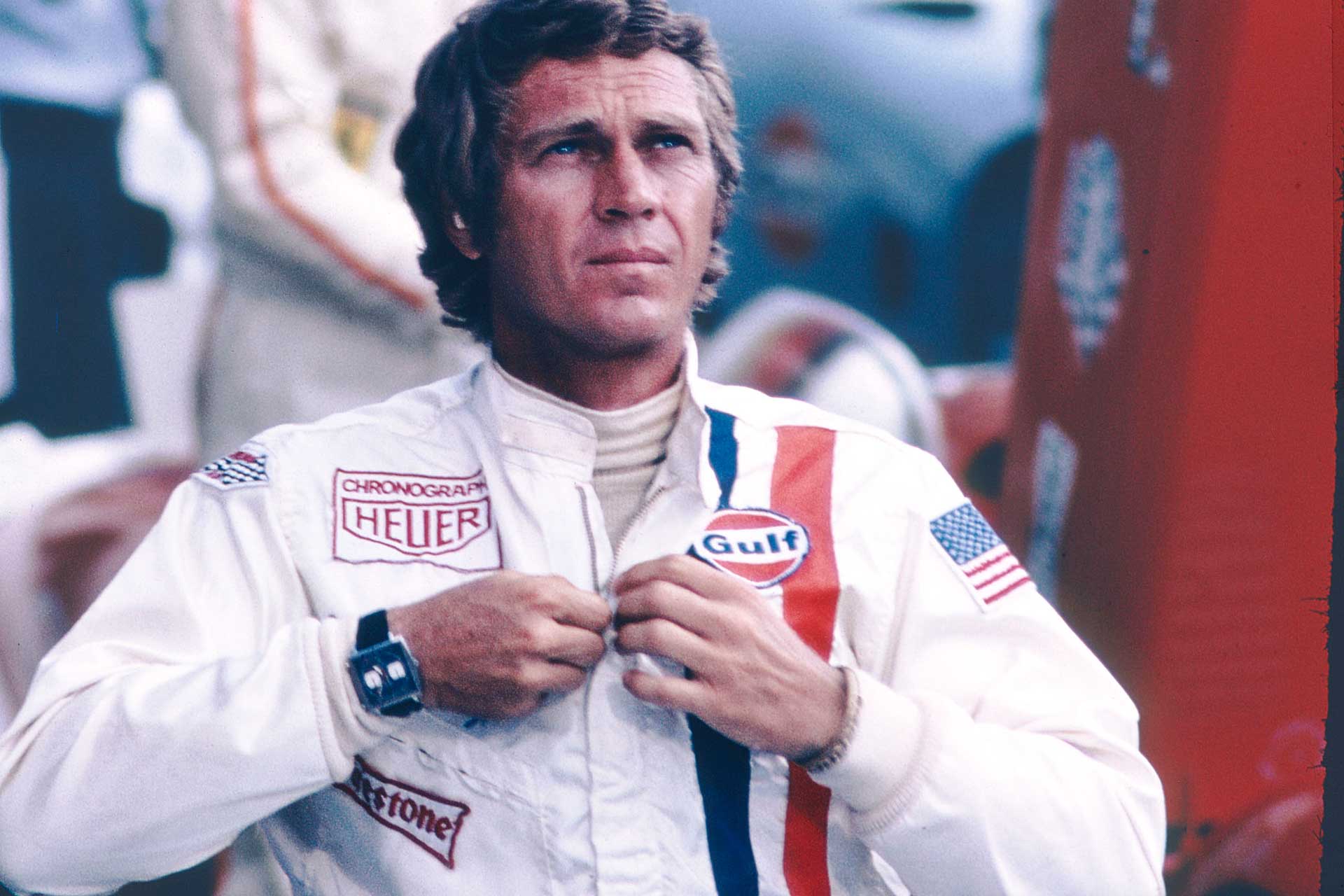

Fit for a McQueen

Steve McQueen, playing the lead character, felt his new friend Jo Siffert was the ideal successful endurance sports car racer. For the Gulf Porsche 917 driving scenes, Steve McQueen wanted to be as true to the original as possible and insisted on wearing Siffert’s driving suit with a large Heuer logo on the chest. Now he needed a Heuer watch to replace his old Rolex Submariner. Rumour has it that it was the cutting-edge design of the Monaco, which persuaded McQueen to wear the blue-dialled version in the film.

Gerd Rüdiger Lang, later the founder of Chronoswiss Watch Company, was a young watchmaker at Heuer in the mid-1960s. During weekends he worked as a professional race timer and was, unsurprisingly, the man selected to supply Heuer wrist- and stopwatches to the property master of the film crew. Heuer products were present for a fantastic 16 minutes of the film and this starring role certainly helped create the legend that now surrounds the Monaco.

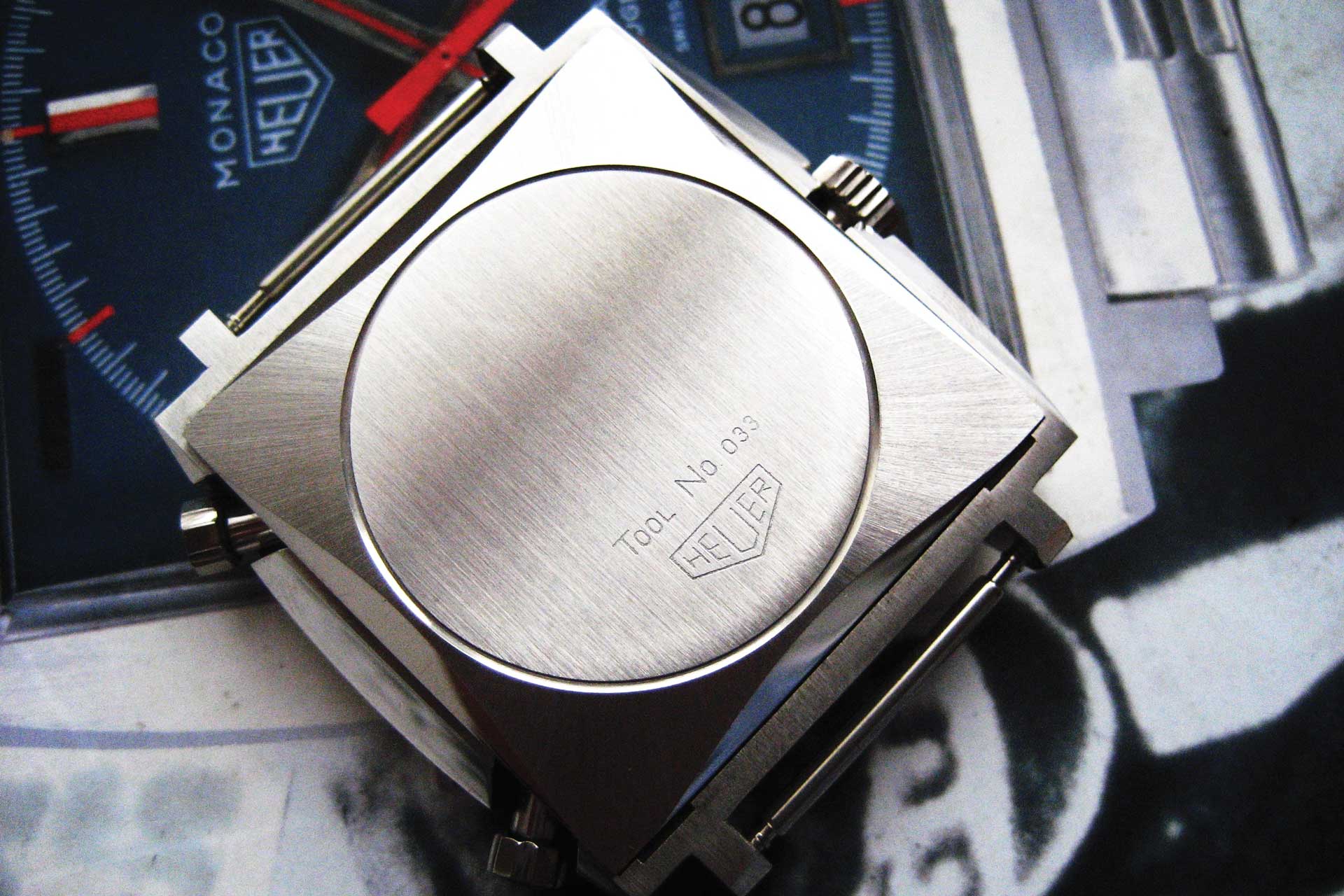

Initially, two Monaco references were launched – the ref. 1133B (blue dial) and ref. 1133G (grey dial). Heuer watches had easily explained reference numbers: 11 was short for the Calibre 11 movement and 33 for Monaco (3) steel (3) series. On the caseback, “Tool 033” was engraved, referring to the opening tool number.

Changing Faces

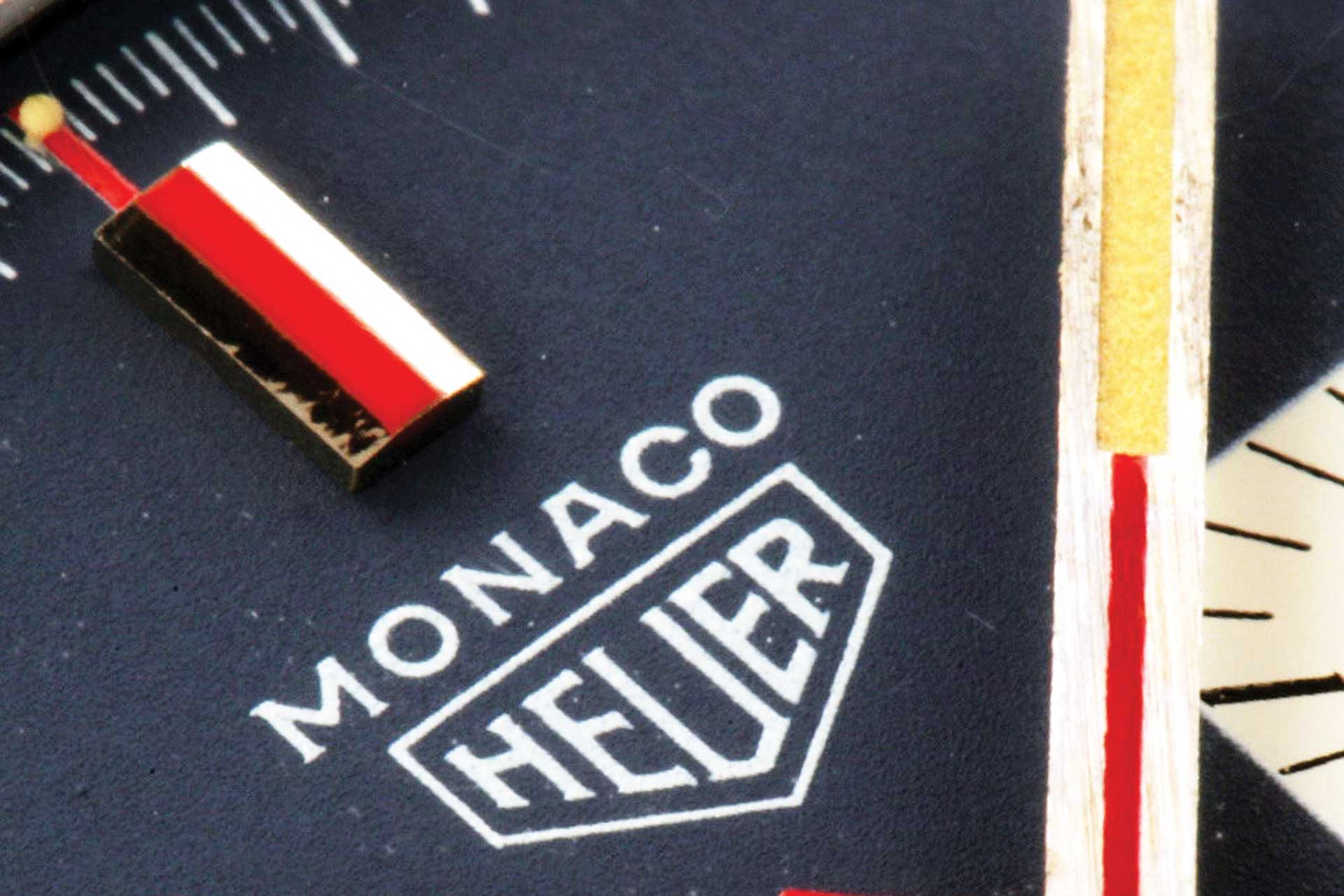

Reference and serial numbers are finely etched on the case, between the lugs at 6 and 12 o’clock, respectively. The very first presentation samples had “Chronomatic” (short for Chronograph and Automatic) above the Heuer logo and the name “Monaco” across the bottom of the dial. This was soon changed when Jack Heuer agreed with Willy Breitling to transfer the name Chronomatic to the Breitling brand – a partner during the development of the movement.

The name “Monaco” was moved to the top half of the dial, above the Heuer logo, while “Automatic Chronograph” was printed in two lines above the silver date window. The rectangular contrasting sub-dials, with minutes and hour registers, were perfectly integrated in the harmonious design. While the early watches were fitted with square polished steel hands, brushed ones with red triangular tips matching the outer scale and markers became standard.

The first dials had a grained finish, the blue paint having a distinctive metallic cast; soon after this was changed to a blue matte finish. All dials had a 1/5-second division, polished bevelled metal hour indices and a large steel index with red print at 12 o’clock. The hour markers had luminous dots for visibility in darkness. The new shock-protected automatic movement used 17 jewels and an unbreakable anti-magnetic mainspring. One distinctive feature was the left-sided placement of the winding crown, which highlighted the fact that with an automatic chronograph, the user would use the crown only on rare occasions.

In 1972, Heuer launched an economy version of the Monaco, references 1533B and G with blue or silver dials. Powered by the Calibre 15 movement, the hour registers were deleted and a tiny seconds hand was positioned at 10 o’clock, with the Monaco model name printed underneath. There is little doubt that the most highly regarded Heuer Monaco is the one with the matte blue dial that Steve McQueen wore in Le Mans. It is ironic that the Monaco was intended to conquer the US market and finally arrived – although with less impact than originally intended – directly in the heart of Hollywood, purely by coincidence.

The growing Monaco product line included both automatic and manual-wind versions. With three sub-registers and no date, the hand-wound models offer a harmonious dial design including a running second hand at 9 o’clock. First shown in the 1970/71 Heuer catalogue, some believe that these models are really undervalued today, compared to their automatic siblings. These watches, with the reference numbers 73633B and G, carried respectively blue and grey dials with contrasting sub registers, and were fitted with Valjoux 7736 movements. As before, the reference numbers were engraved between the lugs and “Tool 033” can be found on the back.

The 73633 cases had similar dimensions to the other models, but the crown was relocated back to the classic position between the fluted chronograph pushers. In the 1972 catalogue, an elegant all-grey dial version was shown.

In 1974, new models of the Monaco were introduced with the reference 74033. The dial design and configuration were similar to the 1133 automatic, with separate registers for hours and minutes and a date window at 6 o’clock, but with no indication for the running seconds. The watch was powered by a Valjoux 7740 manual wind movement, its winding crown located on the right-hand side between the fluted chronograph pushers.

Black Watch

Heuer began slowly to phase out the Monaco models just a few years after launch: the Quartz Crisis had struck and the industry reacted by producing bold 1970s designs. Nevertheless, Heuer made a final attempt and fitted an all-black dial. The minute and hour hands were contrasting white, while the chronograph hands were all shiny red-orange. The Monaco’s steel markers were now replaced by luminous bars and the steel case was coated black. The dial configuration was the classic minutes and hour design with the framed date window at 6 o’clock. The movement was the hand-wound Valjoux 7740.

Research shows that this version never reached the market in big numbers. It was also made evident after discovering a rare order document from one of Heuer’s main markets that the reference 74031NC was given to this utterly uncommon model. The number 1 in the reference stands for black, as does N (Noir) C. To find an original example today is a bit like winning the lottery. Due to its scarcity and its special look, it is for some the ultimate Monaco to have in a collection.

I have spoken with both Jack Heuer and Gerd Rüdiger Lang, taxing their memories about production volumes on Monacos. They both estimate that approximately a couple of hundred pieces were made per year. What is interesting is that both suggest that this was due to the Monaco being ahead of its time and its polarising design.

Good specimens have become rare and demand by far exceeds supply, resulting in steadily climbing prices over the years. During the early years there was a production issue with sticky seals ruining the dials, which means fewer perfect examples have survived. The automatic references 1133 and 1533 were preferred by customers, resulting in more automatic versions being produced. The estimated split is two-thirds automatics to one-third manual-wind.

Watch specialist and auctioneer Paul Maudsley, says: “The market for vintage Heuers and in particular the fabled Monaco keeps growing year-on-year. It appeals to new and old collectors alike with the striking designs and fascinating historical links to motor racing. The Haslinger Collection, which I sold at auction in 2010, was not only a benchmark for prices, but also for people’s perception of the brand. The auction doubled the pre-sale estimate with a packed saleroom and international telephone bidders all wanting to win the special pieces. The funny thing is that the hardback auction catalogue is still in demand. I anticipate an ever-growing demand for the best examples of vintage Heuer Monacos in the future.”