Ian and I had the recent pleasure of visiting the high-end Portuguese jewelry brand Eleuterio in northern Portugal, which specializes in a contemporary interpretation of the local traditional art of filigree.

“Filigree” is a word we sometimes use when writing about watches to describe intricate and delicate metal work, whether as decoration in the movement or as stand-alone artwork (the Vacheron Constantin Ottoman Architecture Fabuleux Ornemants springs to mind as a perfect example of the way we use this word in watches).

However, this contemporary way of using filigree as an adjective is not the only way it can – and should – be used. “Filigree” is first and foremost a noun denoting ornamental jewelry work, typically using fine gold or silver wire that is artistically formed to make a pattern of delicate tracery.

Ancient examples of early filigree jewelry on display at Travassos’s Museu do Ouro; at that time coins were often turned into wearable jewelry

As archaeological finds have indicated, filigree jewelry has been made since as early as 3,000 BCE in Mesopotamia. This jewelry featured silver and gold wires and was known as telkari. To this day, regional specialists in the Middle East, Kosovo, Albania, and Turkey continue to work with the art form.

Filigree also continues to exist in Egypt and India, where experts think that it is quite likely that the designs have not changed significantly over the centuries.

Other historic places where ancient filigree objects have been found include Phoenician sites in Cyprus and Sardinia, which is how experts conclude the art form found its way to mainland European cities such as Porto, which has a major trade waterway in the Douro river. This river was a key thoroughfare used to transport Port wine to England and other places as Ian explains in 5 Things You Should Know About Port Wine But Probably Don’t, Including Why You Don’t Want To Know The Bishop Of Norwich.

Ancient examples of early filigree jewelry on display at Travassos’s Museu do Ouro

Filigree jewelry has been present in a variety of European cultures since medieval history, and while it has largely declined or even died out in most places, in northern Portugal it has remained an integral part of contemporary culture.

Portuguese filigree in the Porto region

In the Middle Ages the manufacture of filigree objects was widespread among cultures bordering the Mediterranean, including the Moors of Spain. And while it is possible to still find examples of filigree in Italy, Malta, Macedonia, and parts of Greece, among other places, Portugal today remains the seminal European location for high-quality filigree jewelry.

An ancient goldsmith’s bench inside the Museu do Ouro in Travassos, Portugal used to make filigree jewelry

The use of filigree in Portuguese objects dates back to the early Middle Ages when ancient Celtic tribes heavily influenced the Porto and Braga regions. Celtic place names like the Douro, which originates in the name “Durius” from the Celtic dur (“water”), abundantly remain as a reminder of the tribes who saturated the coastal Iberian regions. Ancient minted coins continue to be unearthed as examples of archaeological treasure.

Porto, Portugal’s second largest urban settlement after Lisbon, is a delightful Iberian city whose roots date back to around 300 BCE with Proto-Celtic habitation. An important commercial port of the Roman occupation, Porto’s most important trade partners were Lisbon to the south and Braga in the hinterland of Porto.

The export of the excellent Douro Valley wine famously originating in this region dates back to approximately the thirteenth century, as far back filigree jewelry. But it is actually the Braga region that boasts the artisans responsible for some of the world’s best filigree jewelry.

Ancient goldsmith’s tools inside the Museu do Ouro in Travassos, Portugal used to make filigree jewelry

And it’s no accident that Portugal’s filigree “industry” thrived here: it is near both the erstwhile gold mines of Gondomar (supply) and the river Douro (transport to Porto).

“Where there is gold, there will be goldsmiths,” António Moura, CEO of Eleuterio, reminded me during our recent visit to Porto, Braga, and Travassos to learn more about this art form.

Travassos, one of the main hotspots for filigree jewelry-making, is a sleepy little village with 700 inhabitants outside of Braga that is like a warmer version of the Swiss countryside in the Jura, where the watch factories are located. The village of Travassos has two claims to fame: the first of which is that it is home to what is most likely the world’s only private museum dedicated to the art of filigree jewelry, Museu do Ouro.

Inside the Museu do Ouro in Travassos, Portugal

The Museu do Ouro, open by appointment only, dedicates itself to the history of filigree in the region. In a previous life, the historical building was the workshop of a multi-generational family of goldsmiths.

And not only are all the traditional tools and furniture still set up in the museum as they would have been used, but there are also 50 years’ worth of gold objects and literature collected by goldsmith Francisco de Carvalho e Sousa to study, ponder, and discuss.

The second reason to visit Travassos is that it is also home to Eleuterio, a brand that is most likely the most luxurious jeweler working in filigree today. Eleuterio represents a refined, contemporary interpretation of the ancient filigree technique.

A view to the Eleuterio workshop (white building on the left) in Travassos, Portugal

But before we get into Eleuterio’s specific designs, let’s take a look inside the 90-year-old marque’s Travassos workshop and see how filigree is made.

How the “angel hair gold” (aka filigree wire) is made

Filigree, a word that originates in the Latin words “filum” (“thread”) and “granum” (“grain”), is a great use of gold, not only to “stretch” the precious material – so to do more with less – but also because it makes gold jewelry lighter and easier to wear without losing any ideal of value or design.

In other words, the filigree technique allows the material to be solid, while at the same time looking more delicate than it actually is. Filigree jewelry is lighter and more comfortable than a solid piece of engraved gold.

The foundry of the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal

In a nutshell, filigree sees fine gold or, traditionally, silver (but not at Eleuterio, where only gold is used) wires rolled into spirals (“snails”), pressed into place, and often decorated in some way. Filigree is a technique requiring steady hands and a great deal of experience to artfully produce.

Ian and I were extensively walked through the process by Moura, Manuel Duarte (the goldsmith responsible for Eleuterio’s workshop), and company president Luis Antunes, the grandson of the founder, who revealed three main secrets to the creation of filigree at the outset: create good wire, work passionately with the wire, and solder it carefully using experienced hands and trained eyes.

Tools in use at the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal

“The art of filigree is really the art of soldering,” Antunes emphasized regarding the very traditional technique that is still alive and well at the Eleuterio workshop. This is an art form that cannot – and should not – be industrialized.

There are 65 total steps needed to obtain a gold “thread” that is close to the diameter of human hair.

Inside the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal: 18-karat gold being melted

The creation of this fine wire starts in the foundry with a small solid bar of 18-karat gold that is melted into liquid at around 1,000°C. Crazily enough, this gold is quenched after heating, which is something I have only seen with steel up to now. Sixty grams of gold creates about 100 meters’ worth of wire.

Inside the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal: quenching 18-karat gold

Then the gold bar is squeezed, heated, squeezed, heated . . . you get the point.

Manuel Duarte squeezes the 18-karat gold bar through a machine called a laminator, which makes the bar ever longer and thinner so that it can be drawn into fine wire

The drawing machine (banco de puxar fio in Portuguese) is an interesting point of reference because we saw a vintage example that was hand-operated at the museum as well as a new electric model in the Eleuterio workshop, which made comparisons between the modern era and those that came before easier to visualize.

Drawing the 18-karat gold into ever finer wire at Eleuterio

Drawing the 18-karat gold into ever finer wire at Eleuterio

Drawing the 18-karat gold into ever finer wire at Eleuterio

Drawing the 18-karat gold into ever finer wire at Eleuterio

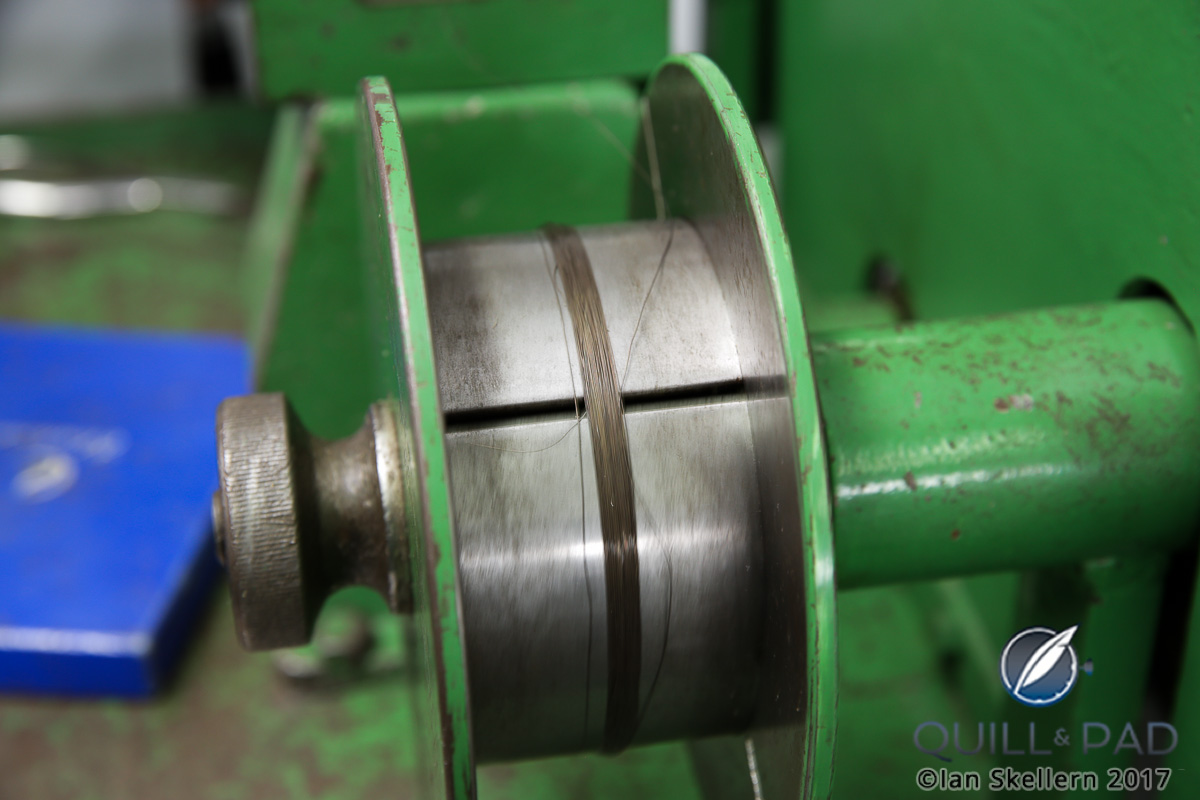

The wire is then drawn in a technical process called trefilagem. Those familiar with the details of watchmaking might recognize this tool as looking eerily similar to that used in the process of making fine balance springs – for which reason I dubbed the instrument in my head “the balance spring machine,” even though the Portuguese artisans call it the carrinho de puxar fio.

The wire is put through the laminator and the carrinho de puxar fio around 30 times each.

Manuel Duarte coils the fine 18-karat gold wire in the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal

When all that is done, two artisans stretch the wire to its full length (reminding me somewhat of a process I witnessed at Hermès’s crystal subsidiary, Cristallerie Royale de Saint-Louis in which molten glass is stretched out by two artisans to make crystal canes), before doubling it and twisting it like a rope.

I thought it looked like more a ultra-fine pretzel dough than rope, actually; the artisans used much the same motion in a step they called torcer filigrane, which they do three times to really tighten the fine wire. And then they heat it again. And twist it again . . . you get the idea.

The fine 18-karat gold wire coiled and being heated in the Eleuterio workshop in Travassos, Portugal

This stretching, doubling, and rolling process shortens the wire so that it shrinks down to 30 meters from the original 100-meter length.

The artistry of soldering

When all that is accomplished, the goldsmiths take pieces of the wire and form them into the famous “snails,” ready for incorporating into the jewelry pieces.

António Moura surveys the intricate work accomplished by Eleuterio’s artisans in Travassos, Portugal

They heat and position the snails, shake a bit of gold powder onto them, and then artfully solder them into place. The heated gold powder melts in the joints and invisibly fuses all of the delicate pieces together.

An Eleuterio artisan at work

A complicated piece of jewelry will take a full work day to properly assemble and solder within the frame of an 18-karat gold ring, earring, necklace, or bracelet element. The frame defines the actual shape of the piece, while the filigree decoratively fills it in.

A look on the bench of one of Eleuterio’s artisans in Travassos, Portugal

One of the artisans sitting along the long bench is a diamond setter, who does all the diamond setting by hand once the filigree has been added to the frame.

An extremely complicated piece of 18-karat yellow gold filigree art fresh off the bench at Eleuterio

Eleuterio: the contemporary art of filigree

Filigree is part of the Portuguese identity; it is an art form as synonymous with the culture as Port wine, azulejo tiles, or pastel de nata.

While traditional filigree is firmly rooted in both religion and commerce – with the most widely recognized and utilized symbol, even to this day, being the Viana heart – Eleuterio has elected to go a different route, thereby bringing filigree firmly into the twenty-first century and the contemporary jewelry scene.

While the extraordinary complexity of the delicate objects ensnare the senses, the traditional Portuguese filigree industry has suffered a bit in recent years for the same reasons that any handmade object (including watches) has suffered: consumers’ search for cheaper prices and brands responding by outsourcing and mass producing.

A traditional Viana heart from Travassos’s Museu do Ouro: this religious symbol represents the Portuguese city of Viana do Castelo as well as devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus

Eleuterio’s concept is to buck this trend in the best tradition of modern Swiss-made watches by bringing value, luxury, and visible complexity back to the art form. And this is why you will find no Viana hearts in Eleuterio’s modern collection.

The brand name “Eleuterio” originates with the name of Rosa and Luis Antunes’ grandfather, Eleutério. It was in 1895 that Manuel Joaquim Antunes began to teach his son, young Eleutério, Portugal’s traditional art of jewelry making in Travassos. Thirty years later, Eleutério opened his own workshop, making 1925 the official founding date of Eleuterio. It was then that he began specializing in filigree.

In 1975 João Antunes took over the company after having worked with his father Eleutério for more than 40 years. Two of his children, Rosa and Luis, continue the family business in the third generation.

Luis Antunes (left) and his 78-year-old father, João Antunes

João Antunes, now 78 years old, doesn’t come to the workshop much anymore even though he still lives in Travassos. For this reason we were especially honored that he chose to visit while we were touring and seemed to delight in our discoveries as much as we did.

Eleuterio’s modern outlook

In 2008, just as the luxury world ground to something of a halt, the siblings restructured – at which time they defined a new strategy that involved redefining and to a degree reinventing the traditional art of filigree to make it more appealing to a younger, more international, and more cosmopolitan clientele.

A necklace from Eleuterio’s Deco Filigree collection

In other words, they – and I – believe that the pieces by Eleuterio should be judged on their own merits, which include filigree, but not just solely on the fact that they are filigree.

Rosa Antunes, Eleuterio’s creative director, most likely wouldn’t appreciate use of the word trend, but, indeed, what she, her brother Luis, along with CEO Moura and visual art director Fernanda Lamelas, have done is to update the traditional art form and bring something new to it. Whether this can at least partially be classified as trendy is something that is best left to the cows in the field next to the workshop to decide.

An 18-karat white gold ring from Eleuterio’s Heritage collection on the author’s finger

What I see is daring addition to tradition rather than trend – this is a place where the art of classical filigree stakes and maintains its claim, but moves over just an inch to give some space to new thoughts, ideas, and emotions that arrive in the form of shapes, coatings, inspirations, contrast, and material use.

To date, for example, Eleuterio is the only traditional filigree producer to utilize a ruthenium coating to make “black” filigree (for more on these jewelry pieces see The Most Glamorous Night In Watchmaking: Eleuterio Filigree Jewelry At The Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève 2016).

Interesting juxtaposition: an Eleuterio Deco Filigree necklace that can be worn on a string of onyx-and-gold beads that strongly resemble a rosary or a gold chain with filigree links

And diamonds: traditional Portuguese filigree does not include the use of precious stones. But Eleuterio’s beautiful jewelry does – and thankfully, because as you surely know, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend.”

But it is important to remember that all of this “newness” can only be accomplished thanks to the skillful experience of the craftsmen (yes, currently all of the artisans working in the Eleuterio workshop are men – I was told that creating filigree in Portugal is still very much a man’s world), some of whom have been working at this workshop longer than Rosa Antunes has been on the planet.

A lovely necklace from Eleuterio’s Blossom collection

One of the goals with this revamping of the brand is the ability to be sold in other markets outside of those like Brazil and Angola that are normally served by traditional Portuguese filigree. This is where Moura’s expertise in luxury watches comes into play: Moura comes from a family of watch distributors and has been in the luxury watch and jewelry business his entire life.

Moura knows that it is of key importance for Eleuterio’s products to be displayed next to other luxury brands, and so he is successfully targeting traditional retail outlets, including the highest-end watch specialty stores and airports.

This ring from Eleuterio’s Heritage collection really puts the intricate filigree wire on display

“This brand is a living treasure,” Moura describes his passionate work. “And it exists because of the artisans; our brand is here to showcase what these artisans can do.”

For more information, please visit www.eleuteriojewels.com.

Disclaimer: Eleuterio paid for flights and accommodation for Elizabeth Doerr and Ian Skellern for this visit.